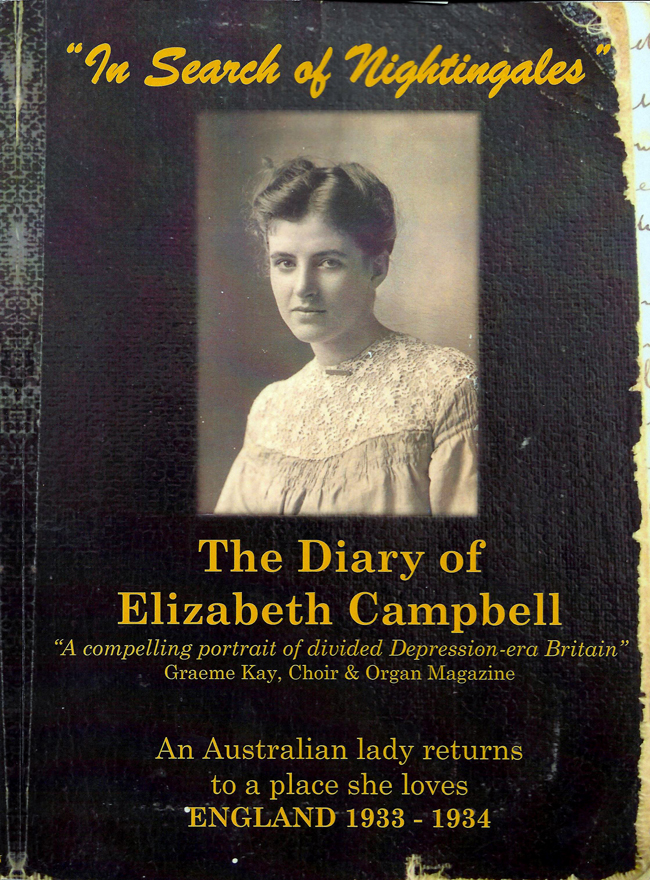

In 1927, Elizabeth Campbell travelled to England from her home in Melbourne, Australia, to study organ and conducting at the Royal College of Music in London with Henry Ley. Heart-broken at having to return, she became one of Australia’s leading organists, but always dreamed of going back to London. In 1933 her dream came true and she was invited back by the RCM as part of their Jubilee Celebrations. She kept a diary of this remarkable year’s visit to the country and city she absolutely loved. The four diary notebooks survived, and have been diligently transcribed – all 1000 pages of them – by Robert Cox, a close friend of Elizabeth’s great-niece, Rosalind Hartshorn.

As Elizabeth writes of the political and musical life of England and London in 1933 she has no idea, of course, that the Second World War is just a few years away. Thus we have a contemporary account of depression-era events and attitudes, unmoderated by hindsight. She hears both Einstein and Mosley give speeches, witnesses the Hunger March as it arrives in London, and approves of Marie Stopes’ revolutionary lectures on birth control. The postman makes 6 deliveries a day, the fogs bring death and traffic chaos to Londoners, and she is upset about the number of beggars on the buses and streets.

For me, it’s the whirlwind account of recitals, concerts, church services around England, accompanied by descriptions of many of the musical personalities of the time, which is the most intriguing. Elizabeth is asked to give several City of London recitals, and auditions for the BBC on their new Compton organ in January 1934. She finds the action on this new-fangled instrument most off-putting, and is convinced she has failed the audition. However she didn’t have to worry – a few days later she arrives home to her flat in Hampstead to find a letter from the BBC asking her to broadcast live on the organ, back to Australia – to be followed by another broadcast live to Canada – the first woman to do so.

She mentions very little music specifically – doesn’t even discuss what she includes in her own recitals, which would be de rigeur for any self-respecting recitalist today. What music she mentions seem to be very mainstream – Elgar, Haydn, Elijah, Messiah, Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, Hiawatha with 1,000 performers at the Albert Hall – though I would have loved to hear, along with Elizabeth, Dame Ethel Smyth’s Prison conducted by Beecham in honour of Dame Ethel’s 75th birthday. She is scathing about organists playing “cheap” music, but doesn’t elaborate. She finds the plainsong at Quarr Abbey lovely in parts but sounding sometimes “like a lost soul, not even vaguely trying to get anywhere” and obviously had not encountered the counter-tenor voice within the English Church tradition before.

Robert Cox says one of of his favourite moments in the diary is when Elizabeth visits Beatrice Harrison’s home in Surrey, for the Nightingale Festival. Cellist Beatrice Harrison had been broadcast by the BBC, in the 1920s, playing her cello in the garden, accompanied by nightingales. This piece of mild English eccentricity was the media sensation of the day, and was perpetuated in an annual Festival in the bluebell woods around Beatrice Harrison’s home in Oxted, when a broadcast van relayed a recording of her cello playing to an amplifier in a tall tree – the nightingales (allegedly) joining in. This is what gave Robert the inspiration for the title of the book, and a YouTube trailer:

In Search of Nightingales: The Diary of Elizabeth Campbell

Editor: Robert Cox

Jaromin Publishing

ISBN 9780954590987

£20

COPIES AVAILABLE direct from The Great British Bookshop