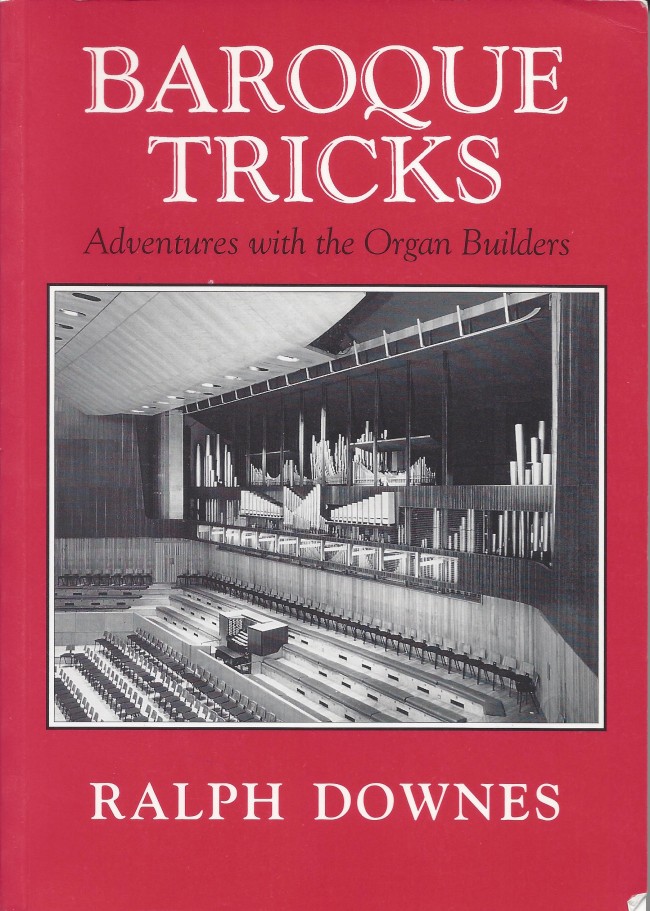

I wish I’d met Ralph Downes. His autobographical book Baroque Tricks, subtitled Adventures with the Organ Builders, is difficult to get hold of now* but gives a vivid impression of the man, and his battles with the organ establishment of the 30s and 40s. Much of the book is taken up with his account of the design and build of the Royal Festival Hall Organ at the Southbank in London, and we will hear the organ tonight in the (sell-out) Inaugural Concert after its extensive rebuild.

Downes’ key gripe against the English organ of the time was that it was not balanced. With strident trebles, an indistinct tenor and muffled ponderous bass, the performance of a Bach fugue with the normal registration of the time (including the use of Great to Pedal Coupler) resulted in a “loud soprano melody with occasional bursts of alto and various mumblings below.” The use of octave couplers on reeds and mixtures was deemed sufficiently ‘flashy’ treatment to do justice to the French style, and full Great plus Tuba was distinguished mainly by bulk or even sheer din – the lack of vitality compensated for by high wind pressures – and so “only loud and rather vulgar in actual effect” according to Downes.

His visit to the Cavaille-Coll at Notre Dame de France in Leicester Square London in 1937 was a revelation. He comments on the “warm but clear, plump, easy speech” of the basses, compared with the sluggish “throttled” sound of English reeds of the time. He tinkered with the organs at the Brompton Oratory (where he was Organist from 1936-77) and Buckfast Abbey, dropping wind pressures, and removing weights on reed tongues, but didn’t have a chance to implement his theories of voicing and winding properly until 1948, when he was invited to be the consultant for the design of an organ for the new concert hall to be built on the South Bank of the Thames – target date the 1951 Festival of Britain.

Initial design was for an organ banished by the Acoustics team into the roof space over the orchestra – happily the Executive Architect at County Hall, Edwin Williams, suggested that the organ be totally visible and accepted as a decorative feature of the hall.

A long series of vacillations followed regarding the organ specification, not helped by the sudden appearance of a large orchestral canopy. Even the finished width of the opening into the organ recess was an issue that remained unresolved until 1952. Numerous sketches went backwards and forwards – the Hall’s interior designers didn’t like the “gothic” appearance of all the pipes on show – each change of aesthetic appearance necessitating a rethink of the organ specification by Downes.

The reactions of the organ building firms asked to tender varied from “enthusiastic desire to co-operate, courteously amused incredulity, and severely admonitory correction”. Harrison & Harrison were chosen (the most expensive) “not because I liked their recently built organs” said Downes “neither did I foresee they would easily adapt to my tonal conception – I know they would not” but because he had “observed their execution of trivial detail (which nobody but the tuner would ever see) in a manner that plainly spelt Perfectionism, no less”. Downes’ confidence in Harrison’s as builders for this project was upheld – in the end, he said, “everything in the new organ was an exemplary model of proud craftsmanship.”

By 1949 the stop list was still conceived largely in a vacuum, since no decision had emerged as to the organ’s front design. A total grille was even being mooted, so the organ could be constructed on “normal good organ-building lines” behind it. Luckily the Leader of the Council, Isaac Hayward, was incensed and indignantly remarked “We are paying for all these expensive pipes and we want to see them as a decorative feature of the Hall.” (The symbolic frontispiece of dummy pipes that then appeared in front of the organ, although approved of by Downes, has been removed in the modern rebuild. I’m sure I’m not the only one who found it rather twee and unsatisfactory.) (Update 18 March: They changed their minds! See my next post.)

The first acoustic tests appalled Downes. The hall had no perceptive ambience whatsoever. A trial orchestral concert by students from the Guildhall School of Music was “dire” – timpany sounding like biscuit tins – though some of the natural reverberation of the hall was recovered by filling up cavities and removal of absorbents. Downes glumly concluded that “at its best, dryness would have to remain a characteristic of the hall’s acoustic properties.”

Downes supervised the tuning, insisting on his own methods being used – it was a struggle as the results at first were “like a direct hit by an aerial bomb on a large farmyard” at his own confession. No one actually said “I told you so” but he knew it was not far off. He persevered – and gradually the organ sound came together – but he always found it dispiriting that the “lovely full resonant tones of the pipes” as they were voiced in the reverberant lobby were “transformed into thin astringency” when restored to the hall’s ambience.

On all the controversy and comment that has followed the Royal Festival Hall organ down the years, Downes said that much of people’s criticism was based on prejudice, and I’m sure there’s a strong element of truth there. He insisted that the Royal Festival Hall organ was not intended by him to set a new fashion – it was a one-off, and he is generous in his praise of everyone involved in a unique project. He did set a new fashion though, kicking off the Organ Reform Movement of the second half of the twentieth century.

And what has the rebuild done for both the hall and the organ? We shall see this evening.

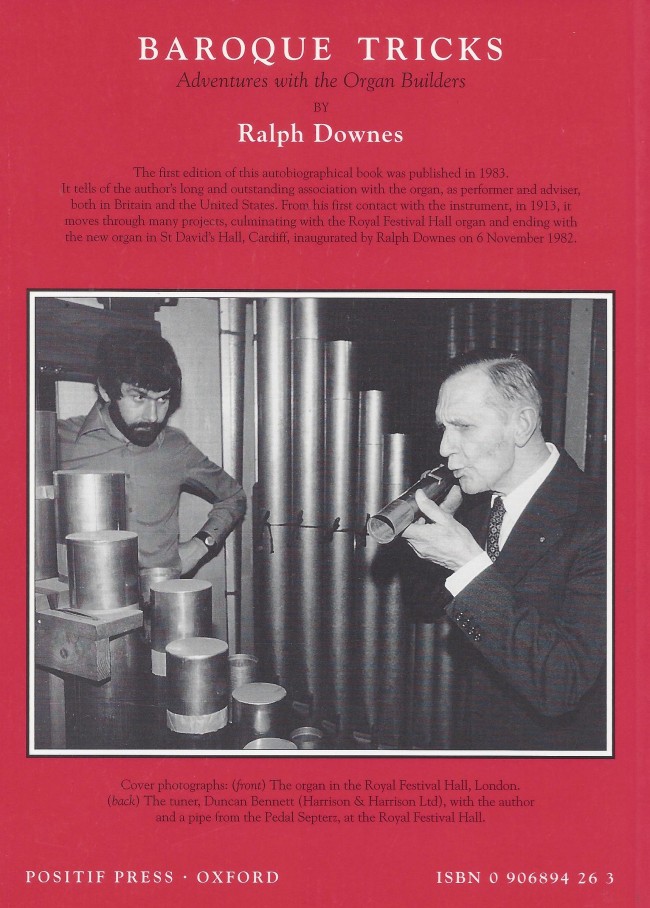

*I’ve quoted Downes here from the book, which is out of print, but occasionally pops up on the secondhand book listings on the Internet. I borrowed my copy from the RCO library. The details are:

Baroque Tricks

Adventures with the Organ Builders

Ralph Downes

Positif Press 1999 (first published 1983)

ISBN 0906894263

Update 19 March 2014: The book is not listed on Amazon, but I noticed Foyles bookshop were selling (new) copies on a stand in the foyer of the Festival Hall at the Gala last night, so perhaps there’s been a welcome reprint.

You can read Downes obituary from The Independent newspaper of January 1994 here

The Southbank’s PULL OUT ALL THE STOPS Festival celebrating the organ rebuild continues until June 2014.

Quite by chance I came across the most interesting article above whilst looking up about AMT!

In 1957 Rqlph Downes was my organ tutor at the RCM. I remember him as a really lovely person though not a brilliant teacher for a middle-of the-road-minus student such as myself! He took the trouble to arrange for his students to have a go at his own Church Brompton Oratory as well as at the RFH.

While still at school one of my teachers treated me to an RFH recital by Helmut Walcha (blind). His wife was an energetic stop-puller!

Tony Poles, BA, ARCO (ChM) eventually!

To have a go at the Oratory and the RFH must have been good! Morwenna

I was not courageous enough to ‘have a go’ at the RFH, but Association colleagues did and acquitted themselves creditably. I was struck then by how patiently and courteously RD received these provincial visitors to the RFH!

I had the good fortune to hear Helmut Walcha play twice at the RFH, and on both occasions he played Bach’s Toccata and Fugue in F, BWV 540 (these must have been in different seasons as RD did not allow duplication of performance of any work in the same year).

Frau Walcha accompanied her husband onto the platform and sat beside him at the console. At first I was very puzzled to see a score on the music desk of the organ but, as you say, this was for Frau Walcha’s use as registrant. I tend to think of these two performances as being in the top ten of all of my lifetime’s musical experiences.

I have the good fortune to possess ‘Baroque Tricks’, personally inscribed and signed by the author. How this came about was due to my writing to the RFH tentatively asking whether my organists’ association could visit the organ. Silence followed for about a year, then unexpectedly the ‘phone rang one evening and a voice said “this is Ralph Downes”, apologising for the lengthy non-response. All was arranged for our visit and the great man played a demonstration programme of music, about eight items as I recall, from the ‘Baroque’ to the Twentieth Century, all with the appropriate registrations. He did allow the use of the general crescendo pedal in some Karg-Elert! He provided a printed programme which he had prepared complete with all the registrations used in his demonstration pieces, Then members were allowed to play and RD listened to them attentively.

Obviously this demonstration by the organ’s designer left no doubt at all about the quality and versatility of the RFH organ (pre-restoration, of course). But RD did say at this later date that if starting afresh he would have used tracker action and the hall itself would have been of an entirely different design. He seemed to ruminate a little and then ventured that his favourite organ was the smaller one which he designed (and regularly played, of course) at the London Oratory, Brompton.

At the conclusion of the visit he said that he had his two last copies of Baroque Tricks for sale, and I was one of the lucky recipients. Two of us were taken by RD literally ‘inside’ the organ, and the books were produced from a small cupboard at the foot of one of the 32’ bass pipes. I noticed then the immaculate finishing which only the tuner would see. The wind chest for the 32s looked like the work of a French polisher.

There’s a sequel to this. The tuner in the photograph on the back cover of the book, Duncan Bennett, was tuning Winchester Cathedral organ (my ‘local’ cathedral) about twenty years later.

The second signed copy of Baroque Tricks was later donated to a mutual friend in Ann Arbor USA, a place also known to Ralph Downes from his pre-WW II time as organist at Princeton University there.

Subsequently I arranged two Association visits to the London Oratory, but by then Patrick Russill had succeeded RD as organist. Patrick Russill speculated how differently the RFH organ would have sounded spread across the west end of the Oratory in that so-different acoustic!