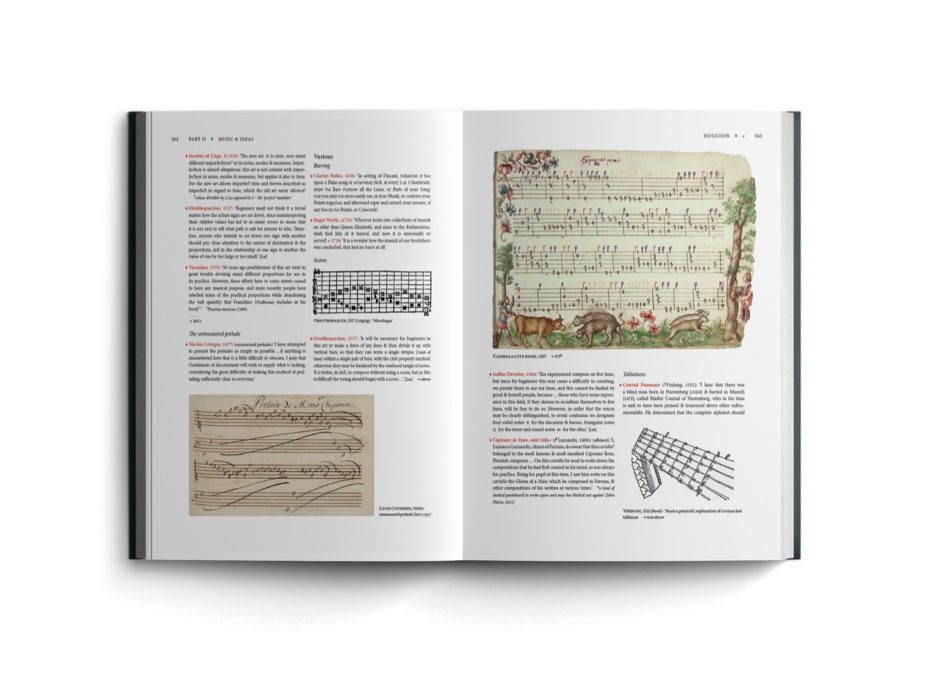

Andrew Parrott (above) is perhaps best known for his pioneering work in early repertory, notably in performances with his own Taverner Consort with whom he has made 60 or so recordings. It is difficult to describe his magnificent new book The Pursuit of Musick with anything but superlatives: here is a treasure trove of commentary on music and musicians exploring 600 years of musical activity in Europe from the first troubadours to the emergence of the pianoforte.

These are the unfiltered voices from the past, and the modern musician will quickly note that, really, not a lot has changed in the business of ‘getting music done’ for all these 600 years. Organists have been moaning about salaries and status, discordant congregational singing, and loose behaviour in the choir, since the church began. The church authorities fussed over polyphony, and then moved on to complain about organists inserting ‘filthie’ songs into services, and showing off their skill by playing for too long.

The leaders of ensembles in court, town or church had the same grumbles then as now: too long hours, too many deputies, musicians past their prime, not enough rehearsal time. Composers have always been disconsolate over players mutiliating their works, professionals have always disparaged the dilettante. And pity the watchmen on the towers of Frankfurt in the fifteenth century, who had to play In Gottes Namen fahren wir (We go in the name of the Lord) every time a boat departed down river.

Happily for us, there is plenty of discussion on the organ and organists, though not always complimentary. Hector Mithobius in 1665 complains that ‘…rather than furthering devotion, organists hinder and impede it by playing runs at inopportune moments, and break up chorales with wierd preluding and random lengthy delays after every line.’ ‘He (the organist) is too often fond of his own Conceits,’ agrees Charles Avison in 1752.

The design and maintenance of organs is commented on: ‘A rotating star with little jingling bells does not belong in a church,’ sniffs Arnolt Schlick in 1511. Werkmeister reckons that the ability to correct trifling defects in an organ (such as a loose screw) ‘is regarded by sensible people as a requirement of an organist.’ Let C P E Bach have the final say on the organ: ‘It lends splendour and preserves order,’ he states firmly, and I’m not going to argue with that.

Our ancestors didn’t spend all their time grouching: lots of fun is had with music (along with eating and drinking). And as well as an insight into the social side of music-making, this book is also a resource for the serious student of historical performance, from tempo, tuning and ornamentation to instrument construction.

With nearly 3,000 entries, and over 500 images, The Pursuit of Musick is not just a book to lose yourself in for an evening, but a valuable collection of of original source material for the specialist. It’s arranged in three main parts – Society, Ideas, Performance – and includes thematic introductions by Hugh Griffith and four distinctive appendices which are an enjoyable read in themselves. Free access to a bibliography and texts in their original languages is given online.

The Pursuit of Musick is available from Taverner, the official website of Andrew Parrott and the Taverner Consort. Full details below.

Musical life in original writings and art c1200-1770

Andrew Parrott

Paperback £35 (also available in hardback £65)

ISBN: 978-1-915229-54-0

available online from the Taverner website